Lake Tanganyika is the deepest lake in Africa and is the largest among the Albertine Rift lakes. The basin has a population of more than 10 million people and the population density within the basin varies between 13 and 250 persons per km2. The countries in the basin are among the poorest in the world. Lake Tanganyika also has one of the richest freshwater ecosystems in the world, with over 2000 species, 500 of them not found anywhere else on earth, making the lake their home. Lake Tanganyika's fisheries yield 165,000 to 200,000 tons of fish per year, employ around 100,000 people, and provide 25 to 40 percent of the protein needs of around 1 million people. The lake is threatened by high population growth, overuse of natural resources, invasive species, habitat degradation, pollution and climate change.

Quick Facts

Bio-physical and demographic characteristics

- Shared by Burundi, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Tanzania and Zambia

- Deepest lake in Africa, and largest among the Albertine Rift lakes

- Surface area = 32,600 km², shoreline = 1,828 km

- Basin has a population of >10 million people

- Population density of the basin varies between 13-250 persons per km2

- Riparian countries are among the poorest nations in the world

Values and investment opportunities

- One of the richest freshwater ecosystems in the world with over 2000 species

- ~500 species endemic, and are not found anywhere else on Earth, and half of these are cichlid fishes

- Total of commercial and artisanal fisheries yield 165,000-200,000 tons per year

- Fisheries employ ~100,000 people and provide 25-40 percent of protein needs to 1 m people

- Lake is known for its ornamental fish as a source of aquarium stock

- Opportunities for cage fish farming, farming on slopes or strips of land between the rift escarpment and the lake, oil and gas development, and tourism in four national parks

Ecological and economic concerns

- Ecosystem services threatened by high population growth, overuse of natural resources, invasive species, habitat degradation, pollution, and climate change

- Rapidly growing population enhances deterioration in water quality of the lake

- Population exerts intense fishing pressure, especially in the northern and southern region

- ~ 30 invasive plants in the basin

Governance

- Riparian countries have institutions to conduct research and implement management measures in development and conservation of natural resources

- Riparian countries have policies and regulations that guide development and conservation of natural resources and are parties to international treaties which bind them to establish mechanisms for managing the threats to biological diversity

- Regional authority LTA harmonizes conservation and management efforts in the lake basin

Potential sustainable development interventions

- Increase awareness through sharing of information and best practices

- Devise internal funding mechanisms for sustainable management of the lake basin

- Scale up alternative livelihood programs to improve adaptive capacity and reduce dependence on vulnerable fisheries resources

- Promote community participation in implementation of best practices to manage resources

Bio-physical and demographic characteristics

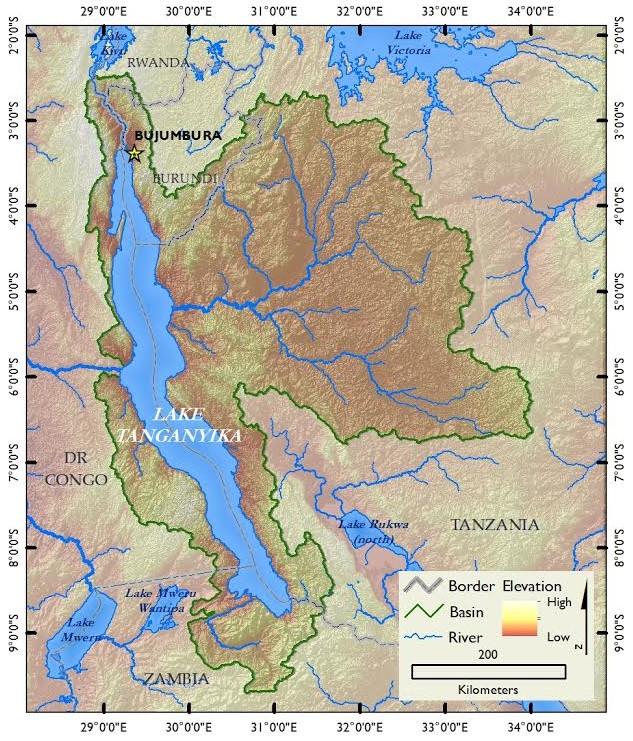

Lake Tanganyika was formed about 9-12 million years ago in the western arm of the East African rift valley. It is located within Burundi (8%), Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) (45%), Tanzania (41%), and Zambia (6%). It has a basin area of 223,000 km2 and extends for 676 km in a north-south direction and averages 50 km in width. It the deepest lake in Africa with a maximum depth of 1,470 m and average depth of 580 m, the second deepest lake in the world, and the largest among the rift lakes with a surface area of 32,600 km2 and a shoreline of 1,828 km. The lake holds an estimated 18,980 km3 of water, which is as much as the five North American Great Lakes combined. It is the largest lake in Africa and second largest in the world by volume.

Despite its large volume, the lake is sensitive to climatic conditions. The climate of the basin is characterized by two seasons; a wet season between October and April, and a dry season between May and September. Rainfall is estimated at 29 km3/year and evaporation at 50 km3/year, therefore, any major drop in annual rainfall and consistent increase in temperature can affect the lake’s water level. The lake may, however, not suffer rapid change in depth because of its large basin and three major rivers adding water to the lake: Rusizi, Malagarasi, and Kalambo (contributing 14 km3/year), as well as the Lukuga River carrying 2.7 km3 of water per year out of the lake.

The population density of the Lake Tanganyika basin varies between 13-250 persons/km2. The full drainage basin has a population of greater than 10 million people which is growing at a rate of 2.0-3.2 percent per year. This is putting much pressure on the resources and is worsened by the small economies of the countries that border the lake, which are among the poorest nations in the world with an average per capita GNP of US $110-320. The lake basin has the poorest and least developed regions of the four riparian countries with low literacy levels, especially in parts of Burundi and DRC where a large portion of the population live on less than US $1 per day. This makes adaptation to environmental stresses such as climate change a major problem. Despite these barriers, the region has registered tremendous progress in fighting HIV/AIDS, whose prevalence is currently 6.4 percent, likely because of donor funding which should be continued.

Values and investment opportunities

Lake Tanganyika is one of the richest freshwater ecosystems in the world with about 2000 species of fish, plants, crustaceans, and birds. About 500 of the species are not found anywhere else on Earth, and 50 percent of those species are cichlid fishes. The lake is, therefore, a unique habitat for biodiversity conservation and evolutionary studies.

Three fish species, Lake Tanganyika Sardine (Limnothrissa miodon), Sleek Lates (Lates stappersii), and Lake Tanganyika Sprat (Stolothrissa tanganicae), constitute the major commercial fisheries. Both commercial and artisanal fisheries yield 165,000-200,000 tons of fish per year, employ about 100,000 people in fisheries related activities, and provide 25-40 percent of the protein needs to one million people living around the lake. The lake is internationally famous in the ornamental fish trade as a source of prized aquarium stock.

Investment opportunities in the lake basin, including cage fish farming; farming on slopes or strips of land between the rift escarpment and the lake; oil and gas development, especially in the southern shores, Ruzizi River basin border of Burundi and DRC and along the north-eastern shore of the lake; and tourism in four national parks—Ruisizi River Nature Reserve in Burundi, Gombe River and Mahale Mountains National Parks in Tanzania, and Nsumbu National Park in Zambia.

Ecological and economic threats

The ecosystem services of Lake Tanganyika and its catchment are threatened by the high population growth, overuse of resources, invasive species, habitat degradation, pollution and climate change. The rapidly growing population contributes to a loss of water quality in the lake. This population is also exerting intense fishing pressure, especially in the northern (Burundi) and southern (Zambia) parts of the lake, where the fishable stock of high-valued Sleek Lates has significantly declined. There are, in addition, about 30 invasive weeds and plants, the major ones being the five floating weeds: Water Hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes), Pistia (Pistia stratiotes), Azolla sp., Lemna sp., and Salvinia molesta. Although these weeds have, as in the case of Lake Malawi, not spread over much of the lake, discharge of urban and industrial waste from urban areas along the shore and agricultural inputs from the steep slopes may change the water quality, especially within shallow areas of the lake, and cause the weeds to increase. For instance, all of the northern drainage area and more than half of the central area have been cleared of their natural vegetation, which is likely to cause more erosion and sedimentation, and a decline in species richness. These threats are made worse by climate variability and change where warming of the lake contributes to a reduction in nutrient recycling in upper layers of the lake, and is accompanied by a loss in primary production and catches of pelagic fish species.

Governance

The lake has a regional organization, the Lake Tanganyika Authority (LTA) to coordinate development and management efforts on the lake. The LTA ratified a Framework Fisheries Management Plan (FFMP) to jointly monitor and manage the shared resources of the lake, and has instituted an Invasive Alien Species (IAS) program to monitor and manage invasive species in the lake and its basin. The countries along the lake have institutions that conduct research and implement management measures in development and conservation of natural resources. The countries also have policies and regulations that guide development and conservation of fisheries and other natural resources and are parties to international treaties e.g. Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna (CITES), Convention of Biological Diversity (CBD), which bind them to establish mechanisms for managing the threats to biological diversity. Non-governmental organizations, such as Tanganyika Catchment Reforestation (TACARE), promote reforestation and conservation education to local populations. A waste water treatment plant has also been installed in Bujumbura to treat 40 percent of urban and industrial water. There are efforts to diversify livelihoods to help increase household income and food security with the hopes that people will be more able to cope with the impacts of climate change.

The above efforts have, as for the other lakes, been constrained by limited funding. Most of the projects aimed at ecosystem restoration have been supported by development partners such as the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Global Environmental Facility (GEF), National Science Foundation (NSF), and United Nations Office for Project Services (UNOPS), which are all short term and cannot be continued after the project funding ends.

Required interventions

The required interventions on Lake Tanganyika are similar to those on Lake Victoria as both lakes have national and regional institutions. These include: networking with other regional institutions; improvement of regional coordination of institutions in development and conservation of the lake and its basin; development and harmonization of enabling policies for adaptive management; devising internal funding mechanisms for sustainable management of the lake and its basin; scaling up alternative livelihood programs to improve adaptive capacity and reduce the dependence on vulnerable fisheries resources; sharing information and increasing awareness; and promoting community participation in implementation of best practices to manage the resources.